Precision molds do not fail due to the fact that there is a single error; they fail due to many little design and manufacturing choices multiplied together over time. Majority of the precision mold failures start when the sample has been taken and not prior to the start of the cycle, or when volume production has gone through, and the cycles accumulate their weaknesses have been discovered such as heat accumulation or resin flow. Dimensional approval at early stages will not ensure the stability of the production process because early tests usually fail to see the effects of the tool on its wear and tear during the regular use. The assumption that most OEMs make is that a mold that passes the first inspection will end up being accurate throughout the production process, and most failures are only realized after repetitive cycles. Failure of precision molds is more a consequence of long-standing design and production choices than just unjustified technical mistakes.

As a senior tooling engineer working on precision mould programs in the automotive and electronics OEMs, I have been involved in dozens of failures which all could be related to neglected details during the design or build stages.

Why Precision Mold Failures Are Often Misdiagnosed

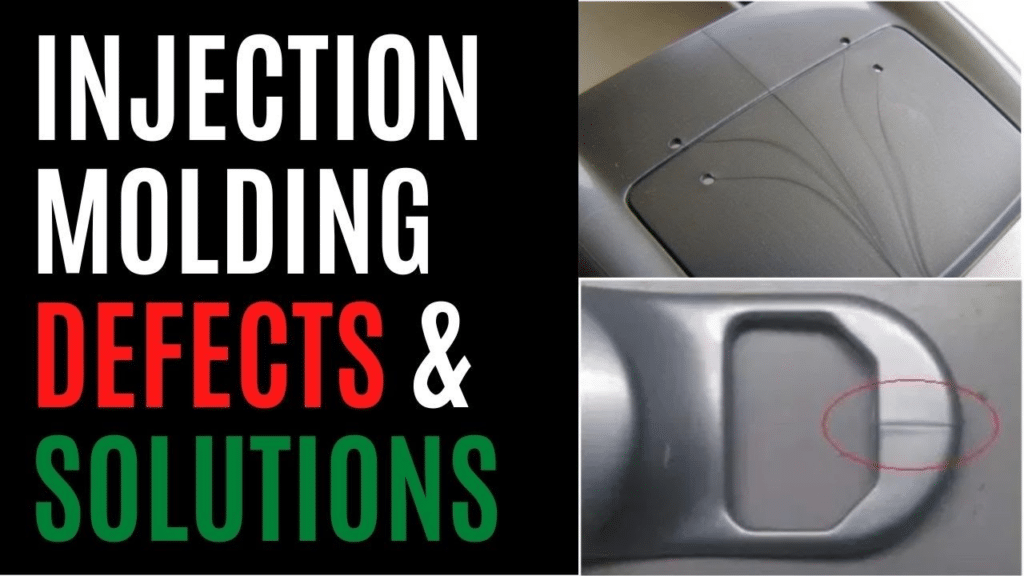

Those cases of precision mold failures are often suspected to be related to the functioning of the tool when in fact, the causes of the problem are rooted in the tooling. It is a typical tendency to attribute any variations in settings or pressure to the operators or pressure variation to the machines, but those are usually the symptoms of the underlying limitations in moulds, like the uneven cooling that can simply require constant changes. The causes are embedded in the design of tools, decisions such as the location of gates or the type of material used that appeared sufficient on paper but do not withstand thermal cycling.

Evaluation based on lifecycle is vital; after 100,000 shots, inspection of a mold shows the existence of drifts, which cannot be detected by sampling. In a single electronics project that I was in charge of, what seemed to be a drift in the process was poor datum control that caused cavity misalignment, and it is important to note that failures have to be systematically not shallowly traced.

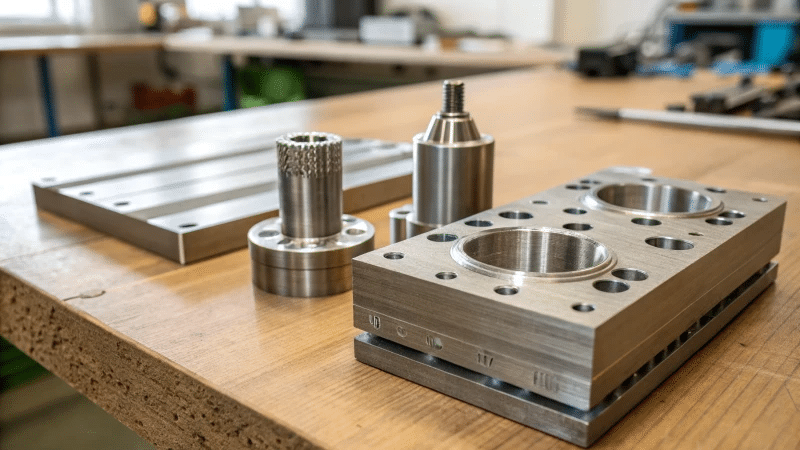

Mistake 1 — Defining Precision by Nominal Tolerances Alone

The definition of precision as just being by nominal tolerances is missing the dynamic character of injection molding and results to a tool that is not stable to maintain specifications in the production process. The drawings of tolerances are known as nominal tolerances, e.g. a core diameter of -0.01 mm, but functional stability looks at the behavior of the part in the assembly due to shrinkage, warpage, and wear. Finding a close set of nominal numbers is a risky behavior that reduces the window of process, and causes a process to be sensitive to small changes in the resin viscosity or clamp force, which further exacerbates defects in the long run.

The misinterpretation of toleration is a common cause of failure in designing tight tolerances which are used without giving critical attributes the first consideration thus creating over-built or under-built areas which crack or deform respectively. I have witnessed molds not passing validation due to nominal focus being insensitive of thermal expansion that result in post-ejection shifts. Proper tolerance planning in precision mold engineering shifts emphasis to functional needs, preventing these pitfalls.

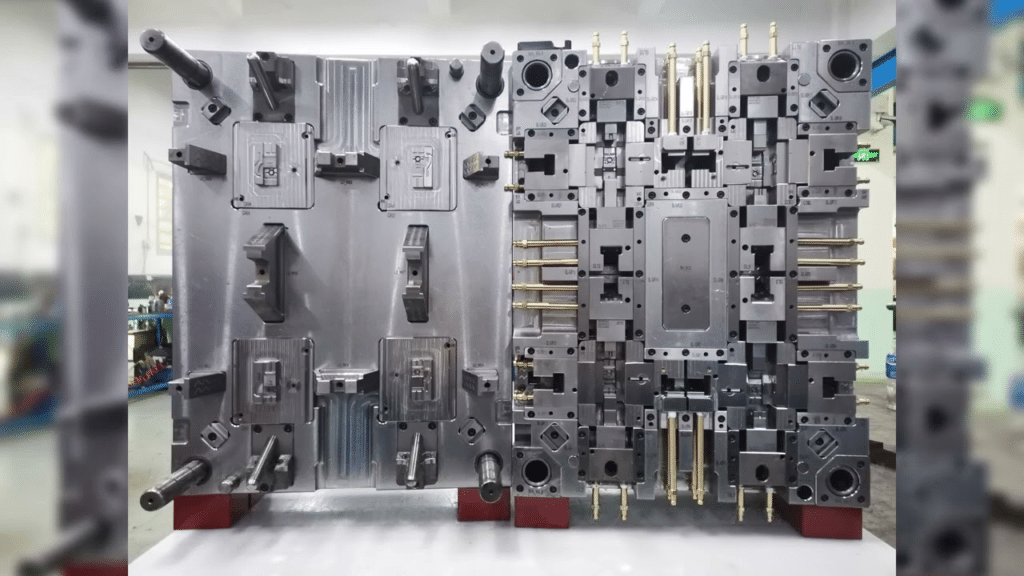

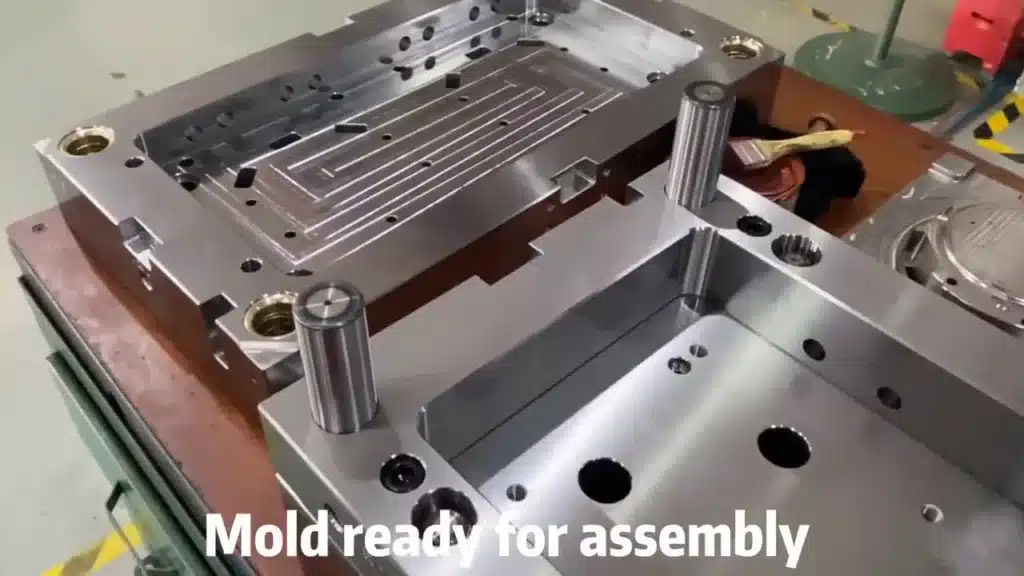

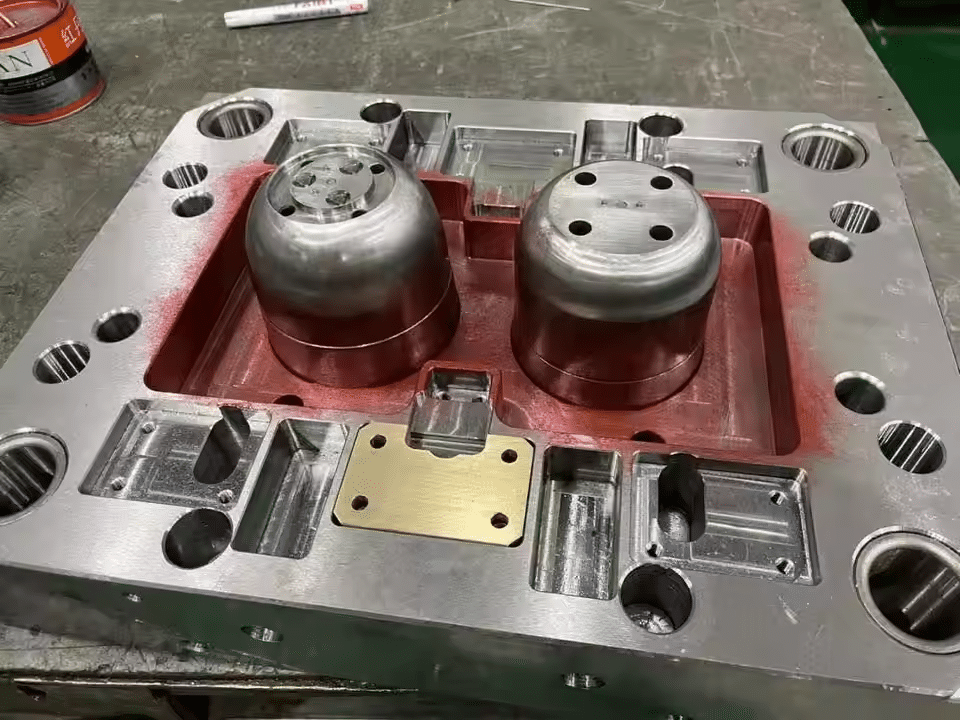

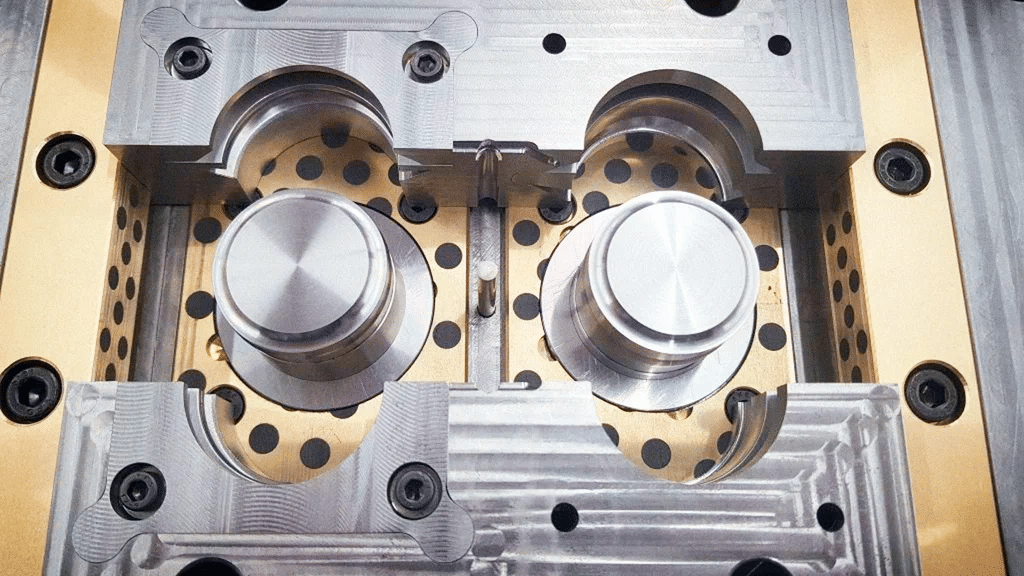

Mistake 2 — Underestimating the Role of Mold Design Stability

Miscalculation of stability in the design of moulds leads to failures that are likely to be recorded in the form of nonuniformity in parts following the first production. Problems with cavity balance occur when runners or gates are not optimised resulting in dissimilar fill rates resulting in short shots in one cavity and flash in another which accumulate to warp as cycles accumulate. The other offender is cooling asymmetry – straight drilled channels may be fine on prototypes, but on precision tools they cause hotspots, which cause residual stresses, which build up over time to diminish dimensional control.

Sensitivity to draft and parting line cannot be overlooked, poor angles will cause ejection or part sticking, and poorly aligned parting lines will produce a flash that must be trimmed, increasing the wear rate on the edges. Minor design oversights, such as not doing flow simulations to save time, accumulate over time into significant problems, such as a 0.05 mm drift after 200,000 shots. In car connectors molds that I designed, balanced cooling was attained at the start of the design, thus avoiding such growths.

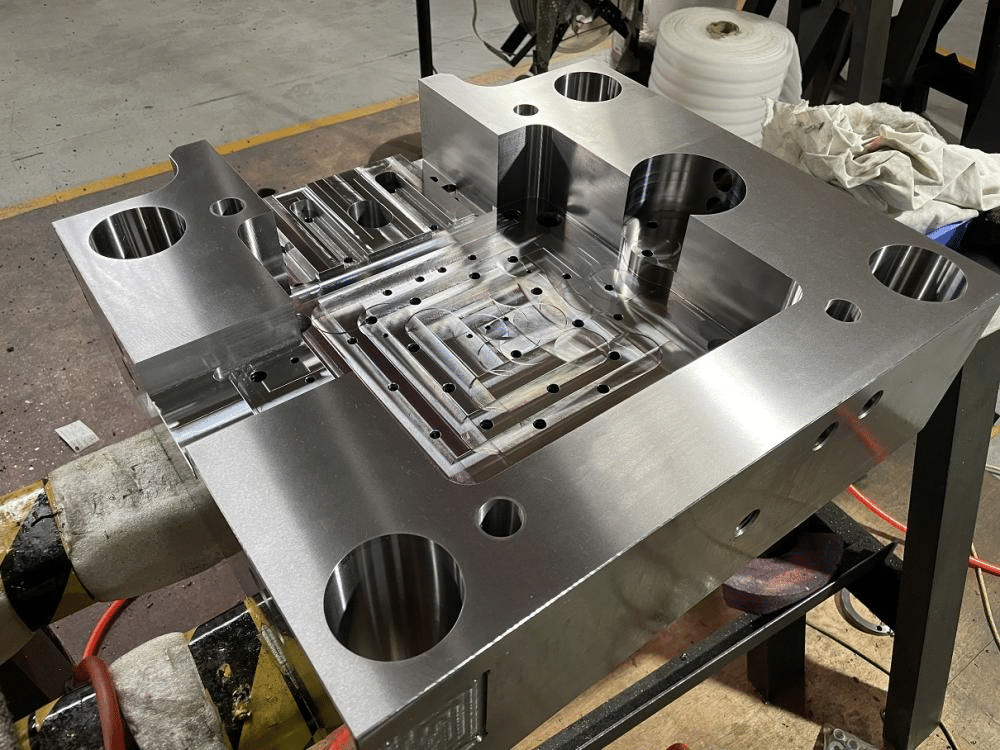

Mistake 3 — Inconsistent Machining and Assembly Control

Uncontrolled machining and assembly creates variance that compromises the accuracy subsequent to the initial cycle. The effect of datum drift is that reference points are not fixed in machining and therefore the errors accumulate in multi-cavity tools as alignments change under pressure. This is enhanced by stack-up errors, the tolerances on individual components accumulate to create total misalignment, which may pass bench tests but in the press, fails.

The lack of a suitable fit and alignment as in loose slide fits or uncalibrated ejector plates will cause flash or uneven walls, and with long time operation, wear of components will be uneven as repeated openings/closings will result in an uneven wear. Relating this to the production process, I have encountered trouble-shooting molds where the error rate of machining dropped by 10 percent after 50,000 cycles as the error in the first few microns grew to a defect.

Mistake 4 — Ignoring Wear, Maintenance, and Lifecycle Effects

The negligence of wear, maintenance and lifecycle impacts hastens accuracy of failure in moulding because gradual degradation is not prevented to occur. Patterns of Mold wear-Mold wear marks of the type visible on gates as erosion by abrasive resins or corrosion in cooling circuits are patterns which get wider with age, and which cause parts to move out of spec, although not visibly broken. The choice of steel and heat treatment is vital; untreated P20 should be used, rather than hardened H13, as it will only cost less in the short run, causing cracks to form faster.

Poorly maintained areas such as absence of cleaning ports to maintain it become obstructions that cause channels to be narrow in domains of cooling, which is unbalanced. One thing that I have learned in the industrial automation tools that I have operated is that unless life cycle simulations are done, the next time that the tool will not be taken off line is after 300,000 shots which is not randomly, but is predictable when done with proper foresight.

How Precision Mold Failures Appear in Injection Molding Production

Failure of precision moulds in manufacturing is usually reported as the reduction in the range of processes required to sustain output with increasing demands on tighter controls. Higher adjustment frequency is an indication of trouble – operators adjusting the pressures or temperatures every day to overcome the drifts, at the cost of uptime. The trends of scrap and rework increase slowly; what begins as isolated warpage turns out to be a systemic issue to the point of increasing the rejection rates into 1-5 percent as wear increases.

Predictability in cycle time is also adversely affected and irregular cooling lengthens holds and cuts down the throughput.From electronics enclosure lines I’ve overseen, these symptoms traced back to design oversights, emphasizing the need for robust production stability in injection molding.

Precision Mold Failure as a System-Level Problem

Precision mold failure is a system level issue in nature in that localized corrective action is very seldom effective since the components and processes are interrelated. The design decisions influence machining feasibility, which has an impact on assembly accuracy, which in turn impacts the maintenance viability, a weak point in one area puts the rest to the test. An example of this is that bad cooling design does not only lead to warping, but also hastens wear in the overheated regions which feeds off of itself.

The interdependence requires the holistic engineering practice between the concept and the decommissioning stage. In the case of medical device tooling that I was involved with, failure had to be resolved by going back to the beginning of the chain, not by treating the symptoms. Adhering to sound precision mold engineering principles ensures systemic resilience, mitigating these interconnected risks.

How OEMs Should Evaluate Precision Mold Capability to Avoid Failure

OEMs are advised to consider the ability of precision moulding by carrying out thorough design checks that dig into the details of surface specifications to understand the risk of instabilities. Understanding the process is important, ask yourself how the mold responds to changes in resin or the environment and use simulations to predict the behavior. Certain signs of lifecycle thinking such as wear notification, or modular repairs point to anticipation of failure.

When sourcing to OEMs I have emphasized the trials under simulated loading of production to reveal weak points early. This aligns with clarifying what defines a precision mold, focusing on sustained performance over initial claims.

Conclusion — Precision Mold Failure Is Predictable, Not Accidental

Precision mold failures do not happen on a whim; they are foregone conclusions of decisions made long before the operations start. By identifying tendencies in the design and production decisions, engineers can no longer respond to the changes but take a proactive approach by using systems thinking to develop products that last. These mechanisms increase awareness, which curbs the risks of OEM, and molds are provided with stable value without failing to meet the expectations.