Both CNC machining and grinding play vital roles in crafting precision mold components, from cores and cavities to ejector pins and sliders, where accuracy directly impacts injection molding outcomes. Yet, declaring one “better” overlooks the nuances of each process’s strengths—CNC excels in shaping complex geometries, while grinding shines in achieving ultra-fine finishes on tough materials. Many buyers assume grinding is always more precise than CNC machining, without considering geometry, tolerance intent, or material behavior. CNC machining and grinding serve different precision objectives; neither process is universally superior for all mold components. The optimal process for precision mold components depends on tolerance function, surface requirement, and manufacturing stability—not on process reputation. As a tooling process engineer who’s spent years optimizing mold builds for automotive and electronics clients, I’ve seen mismatched choices lead to rework or shortened tool life. This comparison unpacks the realities to help mold designers, tooling engineers, and OEMs weigh options based on facts, not folklore.

Why CNC Machining and Grinding Are Often Compared Incorrectly

Historical comparisons between CNC machining and grinding often arise from outdated views of machining as “rough” and grinding as “finish,” leading to assumptions that overlook modern capabilities and hybrid workflows. In reality, this binary thinking results in poor selections—I’ve consulted on projects where teams defaulted to grinding for all tight-tolerance work, only to face bottlenecks on contoured parts that CNC could handle faster. The key distinction lies between form accuracy (CNC’s domain for overall shapes) and surface refinement (grinding’s forte for smoothness), but conflating them ignores how processes interact in a full manufacturing sequence.

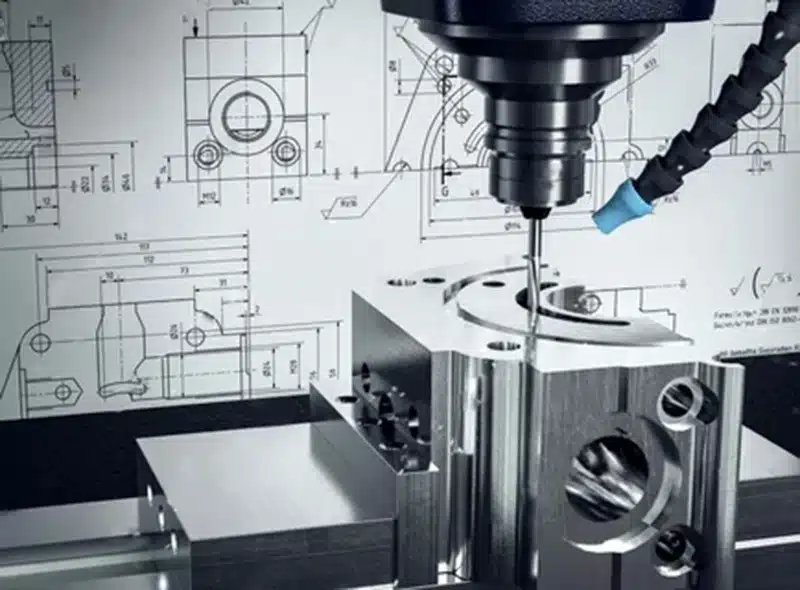

What CNC Machining Does Best for Precision Mold Components

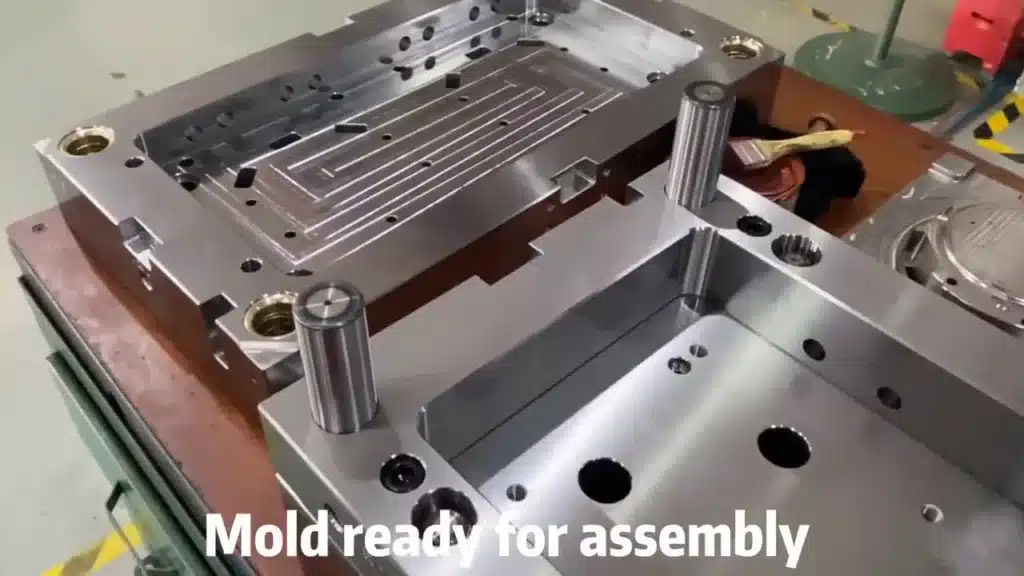

CNC machining stands out for its geometric flexibility, allowing intricate 3D features in mold components that grinding simply can’t replicate efficiently. With multi-axis setups—think 5-axis milling—CNC can produce undercuts, pockets, and curved profiles in a single setup, ideal for complex inserts or sliders where alignment is critical. This versatility reduces assembly errors in multi-cavity molds, and its repeatability shines in batch production, holding dimensions across runs with minimal variance when programmed right.

From shop-floor tweaks, I’ve found CNC’s strength in handling annealed materials pre-heat treatment, avoiding the distortion risks that plague hardened parts. When seeking a comprehensive approach, providers offering a One-Stop Manufacturing Solution integrate CNC seamlessly with downstream processes for consistent results. For specifics on tolerances, exploring tight-tolerance CNC machining for molds reveals how it achieves ±0.005 mm on functional features without over-relying on secondary ops.

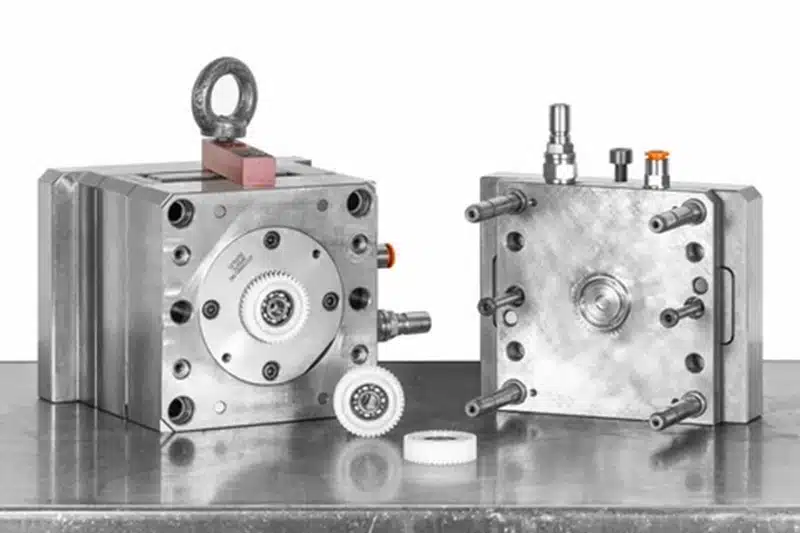

Where Grinding Excels in Precision Mold Components

Grinding truly excels in delivering exceptional surface finishes and dimensional consistency on hardened materials, where CNC tools might chatter or wear prematurely. For components like core pins or bushings post-heat treatment, surface grinding or cylindrical grinding refines flatness and roundness to sub-micron levels, essential for wear resistance in high-cycle molds. It’s functionally necessary when Ra values below 0.2 µm are required to minimize friction and extend tool life against abrasive resins.

That said, grinding’s role is often complementary—I’ve advised toolmakers to use it as a final step after CNC roughing, not as a standalone for complex shapes, to balance efficiency and precision without inflating costs.

Tolerance Capability — CNC Machining vs Grinding

When it comes to tolerances, the debate hinges on functional versus finish types, where CNC often defines the bulk geometry while grinding hones the edges. CNC machining routinely hits ±0.01 mm for overall dimensions in softer states, but grinding pushes tighter on hardened surfaces, achieving ±0.002 mm flatness where thermal stability matters. Grinding refines rather than defines tolerance in most cases—over-relying on it for initial shaping can lead to excessive material removal and time.

In practice, hybrid strategies yield the best outcomes; for deeper dives into limits, reviewing precision mold component tolerances helps align expectations with real capabilities.

Material and Heat Treatment Considerations

Material hardness and heat treatment status heavily sway process choice, as hardened tool steels like H13 demand grinding to avoid tool breakage in CNC ops. Post-heat-treatment distortion—warping from quenching—often necessitates grinding for correction, restoring flatness that CNC might not achieve without risk. Process sequencing is critical: CNC in the annealed state for roughing, followed by heat treat and grinding for finishing, minimizes cumulative errors.

I’ve seen mismatches here cause failures, like cracked inserts from forcing CNC on 60 HRC materials—always map the workflow to material behavior upfront.

Surface Finish vs Functional Precision

Surface finish and functional precision aren’t interchangeable; a low Ra from grinding enhances release and wear but doesn’t guarantee fit, while CNC’s functional cuts ensure alignment even with rougher surfaces. Smoother isn’t always superior—over-grinding can remove beneficial microstructures, increasing brittleness in dynamic components like ejectors. The goal is matching finish to function: mirror polishes for optical molds via grinding, versus machined textures for grip in handling parts.

For tailored options, considering surface finishing for precision mold components bridges the gap between processes.

Inspection and Process Control Implications

Inspection repeatability varies by process: CNC’s digital controls allow in-process monitoring for quick adjustments, while grinding relies on operator feel and post-checks, demanding tighter environmental controls to avoid thermal errors. Process control differs too—CNC benefits from adaptive software for consistency, but grinding’s abrasive nature requires frequent wheel dressing to maintain accuracy.

Matching inspection to process is non-negotiable; strategies like CMM for CNC geometries and profilometers for ground surfaces ensure reliability. Insights from quality control in precision mold components underscore how verification ties back to selection.

Common Misconceptions About CNC Machining vs Grinding

A common fallacy is that grinding always yields tighter tolerances, ignoring CNC’s prowess in complex forms where grinding falters. Another: CNC can’t match fine finishes, yet high-speed milling with proper tooling hits Ra 0.4 µm routinely. Finally, the notion that one should supplant the other overlooks hybrids—both are tools in a kit, not rivals.

These myths stem from legacy practices; modern shops blend them for optimal results.

How OEMs Should Choose Between CNC Machining and Grinding

OEMs should anchor choices in functional requirements, assessing if the component needs geometric complexity (favor CNC) or hardened refinement (lean grinding). Factor material state—pre-hard for CNC efficiency—and tolerance role, opting for hybrids like CNC roughing plus grinding finishing when specs demand both. This logic, drawn from engineering audits, prioritizes performance over preference, weighing lead times and costs rationally.

Conclusion — CNC Machining and Grinding Are Complementary Tools

In wrapping up, CNC machining and grinding each carve out essential niches in precision mold component manufacturing, with CNC driving shape and grinding polishing the details. Viewing them as complementary elevates tooling outcomes, emphasizing integrated planning over isolated picks. In precision mold component manufacturing, CNC machining and grinding should be evaluated as complementary processes, each selected for its specific functional strengths—it’s the balanced approach that delivers durable, efficient molds.