In precision mold manufacturing, the choice of material isn’t just a box to check—it’s the foundation that dictates how well components hold up under the relentless cycles of injection molding. Many buyers fixate on machining precision, assuming tight tolerances will carry the day, but overlook how material behavior under heat, stress, and wear can undermine even the most accurate cuts. Material choice defines the long-term performance of precision mold components more than machining accuracy alone. In precision mold components, material selection determines wear resistance, dimensional stability, and service life more than nominal accuracy. Drawing from years troubleshooting mold failures on the shop floor, I’ve seen mismatched materials lead to premature wear or distortion, turning a promising tool into a maintenance headache. This piece unpacks the essentials to guide mold designers, tooling engineers, and OEMs toward smarter, reality-based decisions.

Why Material Selection Matters in Precision Mold Components

Material selection is pivotal because mold components endure extreme conditions—repeated thermal cycling, high pressures up to 1000 bar, and abrasive friction from molten plastics—that test not just strength but also stability over thousands of cycles. Under these stresses, a material’s thermal conductivity and expansion coefficient directly influence dimensional stability; poor choices can cause warping or cracking, leading to part defects like flash or sink marks. This isn’t theoretical—I’ve consulted on automotive molds where a seemingly robust steel failed due to inadequate corrosion resistance in humid environments, spiking maintenance frequency and downtime.

The link to maintenance is straightforward: materials with superior fatigue resistance reduce the need for frequent replacements, but only if matched to the mold’s duty cycle. For high-volume production, this means prioritizing alloys that resist creep deformation, while low-run prototypes might tolerate less exotic options. Ultimately, getting this right upfront avoids cascading issues, as no amount of precise machining can compensate for inherent material flaws that emerge in operation.

Common Material Categories Used in Precision Mold Components

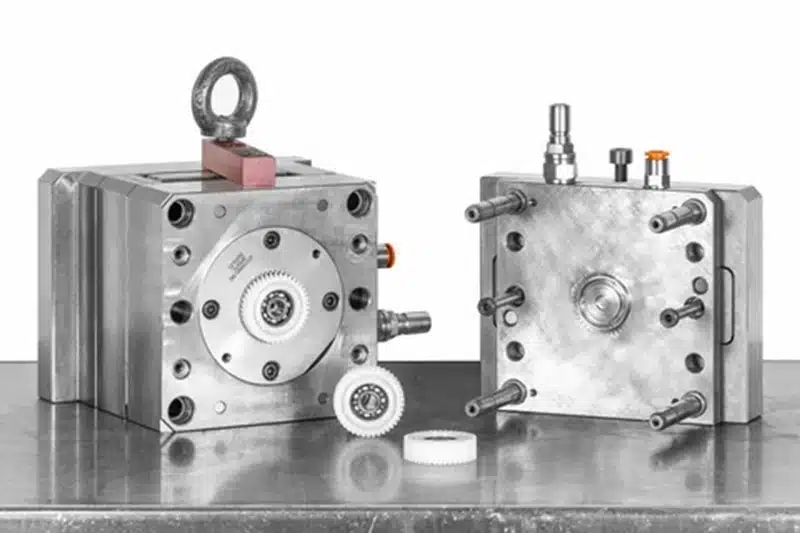

Tool steels form the backbone of many precision mold components, but their performance varies widely between sub-types, demanding careful evaluation based on application demands. Cold-work tool steels like D2 or O1 excel in cores and cavities for ambient-temperature molds, offering high hardness (up to 62 HRC) and good wear resistance against abrasive fillers in plastics. Their strength lies in edge retention for sharp features, but limitations include susceptibility to chipping under impact and higher costs when heat-treated for precision. In contrast, hot-work steels such as H13 handle elevated temperatures in high-speed molding, with chromium content providing oxidation resistance; they’re ideal for ejector pins or sliders in hot-runner systems, though thermal fatigue can shorten life if cycles exceed 500,000 without proper cooling.

Stainless steels, including 420 or 440C grades, are chosen for their corrosion resistance in medical or food-grade molds, where hygiene trumps raw hardness. These materials maintain surface integrity against moisture and chemicals, but their lower thermal conductivity can lead to uneven heating, affecting cycle times— a trade-off that adds 10-20% to costs compared to basic tool steels. Carbide and hard alloys like tungsten carbide stand out for ultra-wear-resistant inserts or punches, achieving hardness over 70 HRC for abrasive resins; however, their brittleness makes them prone to fracture under shock loads, limiting use to low-impact roles and inflating prices significantly.

Specialty alloys, such as beryllium copper for cooling inserts, get a nod for exceptional heat transfer but are reserved for niche cases due to toxicity concerns and expense. Across categories, cost-performance balance is key: tool steels might suffice at $5-10/kg for general use, while carbides push $50+/kg for specialized durability, always weighing against expected mold lifespan.

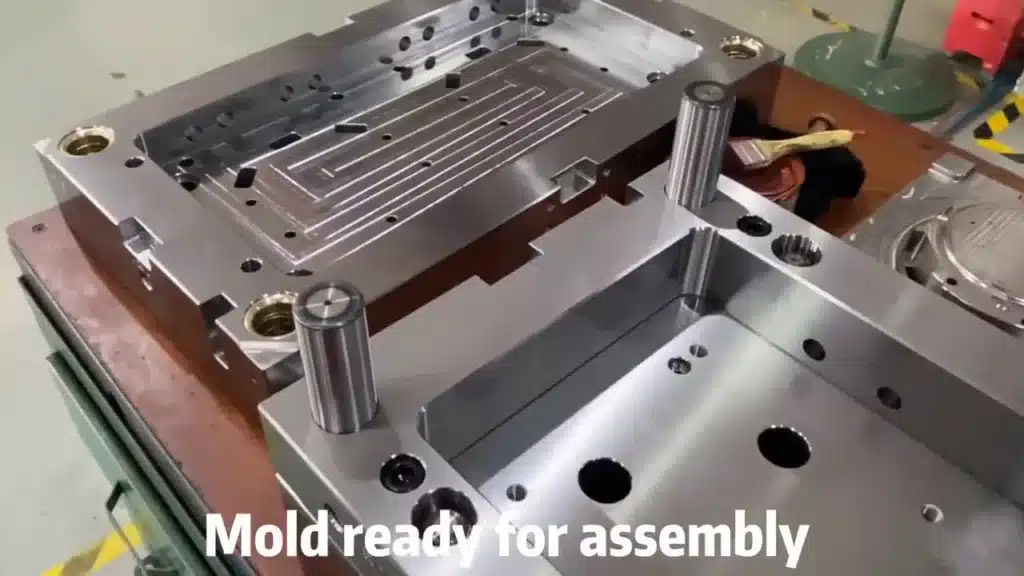

Machinability, Heat Treatment, and Dimensional Stability

Machinability sets the stage for precision, as materials that chip or gum up during CNC operations can compromise tolerances from the start, regardless of machine capability. For instance, high-carbon tool steels like A2 offer decent machinability in annealed states, allowing for clean cuts and stable geometries, but require controlled feeds to avoid work hardening. Heat treatment—quenching and tempering to boost hardness—enhances wear properties but risks distortion; I’ve seen H13 components warp by 0.02 mm if vacuum heat-treated improperly, necessitating post-grind corrections that add lead time.

Dimensional stability post-treatment is non-negotiable for components like core pins, where even minor shifts from residual stresses can misalign molds. Materials with low transformation strains, such as pre-hardened P20, minimize this, holding forms better over time. When assessing Custom Parts Manufacturing capabilities, it’s crucial to probe a supplier’s expertise in material-specific heat cycles and stress relief to ensure stability aligns with design specs.

Wear Resistance, Surface Interaction, and Service Life

Wear resistance in mold components stems from combating abrasive, adhesive, and corrosive mechanisms that erode surfaces over cycles, directly tying to material microstructure. High-chrome tool steels resist abrasive wear from glass-filled polymers, but in material-to-material interactions—like sliders against cores—mismatched hardness can accelerate galling, reducing service life by 30-50%. Surface hardness via nitriding or coatings adds a layer of protection, extending runs to over a million cycles, though over-hardening invites brittleness; for example, pushing carbide beyond optimal levels often leads to micro-cracks under cyclic loading.

Balancing this is essential—harder isn’t always better, as increased rigidity can propagate failures faster in dynamic environments. From engineering reviews, I’ve noted that evaluating wear through accelerated testing reveals true longevity, preventing surprises in production.

Material Selection Based on Application Requirements

Application requirements dictate material picks, as high-cycle molds demand fatigue-resistant options like H21 hot-work steel to withstand 1,000,000+ shots without deformation, whereas low-volume prototypes can use cost-effective S7 for quick turnaround. Precision-critical components, such as optical lens inserts, favor stable alloys like NAK80 to maintain sub-micron flatness, while structural bases might opt for milder 1045 steel for machinability over ultimate hardness.

The balancing act involves cost, performance, and lead time: premium carbides cut cycles but extend procurement, ideal for long-run efficiency but overkill for short series. Engineers should map requirements—temperature exposure, resin abrasiveness—to material data sheets, ensuring selections enhance rather than hinder operations.

How Materials Influence Achievable Precision

Materials inherently shape precision limits, with some offering superior dimensional stability that holds tolerances through thermal swings, while others drift under stress. Low-expansion alloys like Invar maintain accuracy in temperature-sensitive molds, contrasting with standard steels that expand 11-13 µm/m/°C, potentially shifting features by 0.01 mm in hot conditions. This behavior interacts with machining strategies— softer materials allow aggressive cuts for finer details, but harder ones require slower processes to avoid deflection.

Over time, creep in less stable materials erodes initial precision, emphasizing why initial choices matter. For those pushing boundaries, delving into tight tolerance precision machining reveals how material properties constrain or enable ultra-accurate outcomes.

Common Misunderstandings About Mold Component Materials

A pervasive myth is that harder materials invariably extend lifespan, ignoring how excessive hardness amplifies brittleness and failure under impact. Another: assuming one material suits all components, when cores need thermal resistance while ejectors prioritize toughness—mismatches invite uneven wear. Finally, downplaying material impact post-machining overlooks ongoing behaviors like corrosion or fatigue that degrade precision far beyond initial tolerances.

These errors often stem from spec sheets over real testing; shop-floor reality shows materials evolve in use, demanding holistic assessment.

How OEMs Should Evaluate Mold Component Materials Rationally

OEMs should start with functional requirements—defining wear modes, thermal loads, and cycle expectations—before scanning options, ensuring materials align without excess. Matching performance to role means selecting P20 for general cavities but upgrading to H13 for heat-intensive ones, factoring in replacement costs: a cheaper material might save upfront but double long-term outlays through frequent swaps.

This logic prioritizes evidence—lab tests, historical data—over hype, fostering decisions that sustain production reliability.

Conclusion — Materials Define Performance Boundaries

In wrapping up, precision mold component performance begins with material selection; machining quality refines it but cannot override material limitations. Materials set the ceiling for wear resistance and stability, constraining outcomes if chosen poorly. Encourage a system-level evaluation, integrating application needs with material traits for durable, efficient tooling—it’s the engineering edge that turns good molds into great ones.